Chichen Itza Tours: Ek Balam and Chichén Itzá

Hiking . Mexico . Outdoor Recreation . Travel . Worldwide Travel

4 Perfect Days in Mexico’s Riviera Maya and the Yucatán Peninsula (Chichen Itza Tours)

You are viewing Day 4 of our 4-Day Itinerary for Riviera Maya, “Chichen Itza Tours.” Click on any of the days in the list below to view the post for other days. You can also click here to view our full, printable 4-Day itinerary with highlights from each day to help you plan your own adventure along the Riviera Maya.

Things to do in Puerto Morelos Mexico

Mayan Palace & Grand Mayan

Tulum Ruins

The Best Beach in Tulum

Cobá & Pool Day

Chichen Itza Tours: Ek Balam and Chichén Itzá – THIS POST

Planning a trip soon? Use our links to get discounted tickets, rental cars, and more! Our site is partly supported by affiliate partnerships; your purchases through our affiliate links help support our site and the development of even more great content!

Chichen Itza Tours: Ek’ Balam & Chichén Itzá

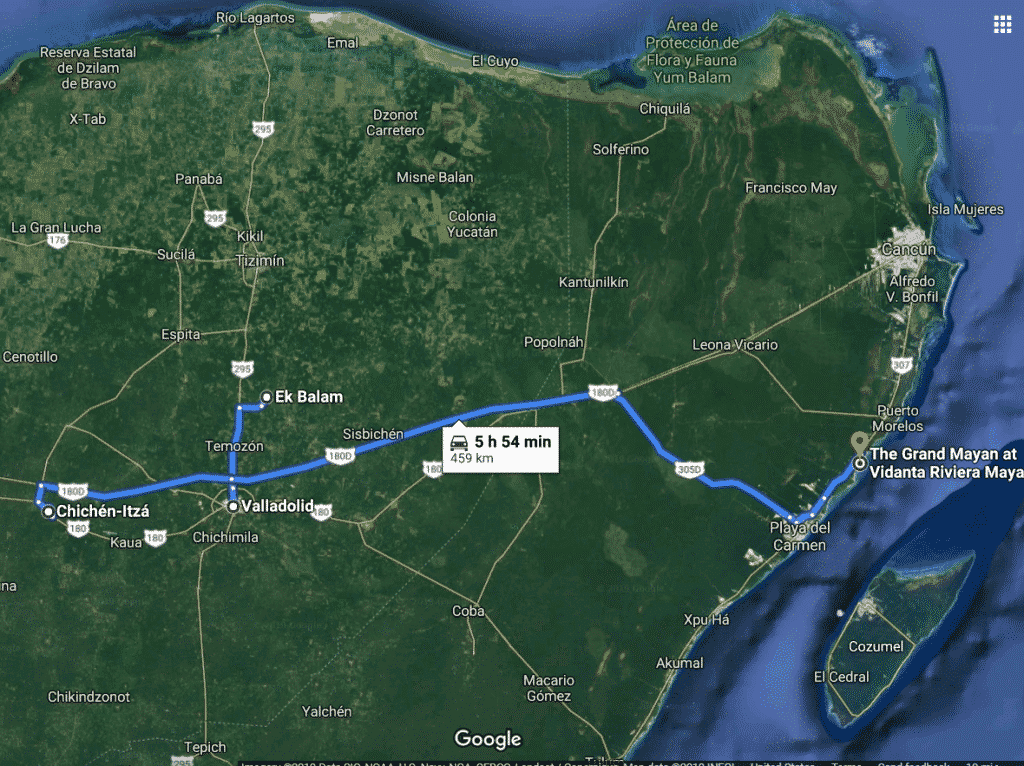

Valladolid is the hub of the Yucatán, and has its own rich, storied history, from Pre-Colombian days to the present. Our two stops today, Ek’ Balam (both the village and the excavated ruins) and Chichén Itzá are both about 30 and 45 minutes North and West of Valladolid, respectively. We’re heading through Valladolid for breakfast before walking around the ruins at Ek’ Balam. Then, we’ll have an early lunch back in town before spending the rest of the afternoon at Chichén Itzá.

In all the drive to all three spots will take about 6 hours of driving, round trip. Unless you plan to stay overnight in Valladolid for your Chichen Itza Tours, there’s really no way around that unless you book a tour and ride a bus or public transportation from Cancun or other stops up and down the coast.

How do You Get to Chichén Itzá and Ek’ Balam? Through Valladolid, of Course!

The drive to the town of Valladolid is an hour and 45 minutes from the Grand Mayan, about two hours from Playa del Carmen. Valladolid is a bustling city with lots of shops and restaurants and other amenities. If you’d like a much more calm, rural town to wander through, check out the village of Ek’ Balam. Several eco-tourism lodges and hotels have opened up recently, and there’s a sustainable farm/retreat/yoga center run by a family that we met years ago on Isla Mujeres. She’s from Germany; he’s from Mexico. Together with their kids, they moved to Ek’ Balam to build a sustainable life for themselves and their guests. Maybe it’s the clear, freshwater cenotes of Yucatán or the warm air and tropical climate; Ek’ Balam and the surrounding area have a disproportionate number of eco-lodges and retreat centers, compared with the rest of the peninsula. Whatever the reason, you’ll have plenty to chose from, and you can book directly online with many of the lodges or through third-party booking agents like our affiliate partner, VRBO.

The Mayan ruins at Ek’ Balam may be less known than their nearby counterpart, but they are no less visually stunning and rich with history. A wide, ample ball court sits at one section of the complex, the primary pyramid structure visible just beyond a stand of trees at one end.

Like many of the other sites closer to Mérida (Uxmal, Sayil, and others), Ek’ Balam features partially re-constructed structures with few visitors and plenty of interior and exterior spaces to explore. You’re likely to encounter bats inside the open stone buildings; the sonic buzzing of my camera flash sent the bats flying in the small room below. Inside rooms like this one, you can see the narrow center stones that hold the rest of the roof in place. Both sides of the roof descend from the center line in a steep pitch, similar to a Roman arch, but without any curvature. This steep, high roof structure is called the Mayan corbeled vault, unique to the Mayas.

Continuing on to the main pyramid, you’ll see numerous thatched roofs lining both sides of the central stone staircase. Underneath are a treasure-trove of sculptures, hieroglyphics, and Mayan calendar inscriptions, expertly preserved and covered in a lime plaster. This is the type of original Maya artifact that you’ll see replicated endlessly at resorts and restaurants all around Yucatán and beyond. Ek’ Balam has some of the most significant and well-preserved examples of various carved images and hieroglyphic writing, so it’s definitely worth a stop and a climb up the steep steps.

Chichen Itza Tours: The Largest Ruins in Yucatán

During the summer and winter solstices, people flock to Chichén Itzá from all over the world to witness the shadows of the pyramid that appear to slither down the sides of the pyramid to the serpent heads that keep watch at the four corners of Kukulkán, the Castillo of Chichén Itzá. (You can watch the Smithsonian’s time-lapse video of the summer solstice “Descent of Kukulkán here). The pyramid is perfectly situated to replicate this effect twice each year during the solstices.

Kukulkán is the Maya variant of Quetzalcoátl, the Nauhatl name for the Plumed Serpent. This deity was one of the most significant deities in the Meso-American pantheon, owing to both ancient legend and myths of historical rulers. Quetzalcoátl/Kukulkán was considered the “morning star,” the creator of the Mayas and the Mexica, and alternatively, the deity of books, learning, and the priest caste. The Spanish and the Mayas alike re-interpreted the legends of Quetzalcoátl and Kukulkan to explain the devastating effects of the encounter between indigenous Mayas and Europeans settlers and conquerors (the Plumed Serpent came from the East, and had surprisingly European features, according to some legends). The so-called prophecy of European arrival as the “return” of the Plumed Serpent served to explain the devastation experienced by indigenous Mayas while justifying Spanish dominance in the region. Both groups benefited from this re-telling of ancient myth.

The first few times I visited Chichén Itzá, the top platform and ceremonial rooms were accessible to the general public. But an ominous sign suggested that dangers awaited the unsuspecting; an ambulance sat ready and waiting near the base of the great pyramid. In the years since, public access to the steps and viewing platform have been restricted, owing in part to the injuries and deaths of tourists who didn’t watch their steps.

Inside Kukulkán, earlier periods of construction are visible, and there’s even an interior staircase that leads to a lower platform with an ornately carved jaguar. When I last viewed this in 2002, the moisture in the completely non-ventilated space dripped from the ceiling and walls.

Circling around the main pyramid, you’ll come to a massive ball court with high, vertical walls and stone rings perched far above the surrounding field. This is actually the largest ball court in all of Meso-America, complete with multiple viewing platforms for royal observers, graphic carvings depicting sacrificial victims, and high stone walls that cast long shadows over the field.

The goal of the game was not only to pass the ball through the small stone rings on either side of the court, but to keep the ball moving back and forth in imitation of the planets and solar bodies. Each of the temples to the North and the South are decorated with different reliefs, some depicting families or clans, warriors, sacrifices, decapitation, and other practices.

The carved skulls are what the Aztecs called a Tzompantli or Row of Skulls. This carved version of the actual skull racks is a much more human-friendly version of the tzompantli found in Central Mexico.

Below, stone serpent heads protrude at the top of the platform of the Eagles and Jaguars. The platform base depicts different images, animals, and practices, like this eagle and jaguar eating human hearts.

Chichen Itza Tours Pro Tips: What To Do (And What Not To Do)

As I’ve mentioned the last few days, for your Chichen Itza Tours, it’s well worth hiring a local guide for the mix of local knowledge and perspectives, and it supports Maya communities in the area directly. And just like Cobá and Tulum, we recommend buying one of the official site guides for reference and for future information. It’s pretty fun to read more in depth about where you’ve been, either by the pool, on the beach, or on your flight back home. The guides are written by archaeologists and researchers at the sites, so that’s the very best, most accurate source of information about the sites.

Because it takes a while to drive to Chichén Itzá (unless you’re staying in Ek’ Balam or Valladolid), just expect to get rained on at some point. Take an umbrella; even though the rain feels pretty good in the humid tropical heat, you don’t wan’t to spend the drive home sopping wet.

You can view the Gran Cenote at the site, but it’s not accessible like many of the clearer fresh-water cenotes elsewhere throughout Yucatán. Even though we ran out of time today, you could add on a refreshing stop at a nearby cenote, either here or closer to the coast.

Small statues and a Chac Mool, god of rain, sit above the steps to the temple of the Warriors. This temple is visible from Kukulkán and the direction of the ball court. The jaguars, eagles, and mythical animal in the murals are all depicted eating a human heart. The Chac Mool at the top of the stairs may represent a mediator or intermediary between the Maya and the gods. Murals inside the temple depict daily life, human sacrifice, and battles. The ominous clouds that formed as we walked around the complex definitely added to the mystique.

Near the Temple of the Warriors, you’ll see the Temple of the Tables and Temple of Chac Mool. Murals in these temples depict jaguars and seated male figures on jaguar thrones. The Temple of Chac Mool is located beneath the outer structure of the Temple of the Warriors, and the Temple of the Tables sits just to the North of both, on a separate platform. The Group of a Thousand Columns flanks the three temples. This enormous, column-supported roofed area likely served some military or training function. More than 2,000 images of armed warriors mark each of the supporting pillars.

What is the History of Chichén Itzá, and What Were Chichén Itzá’s Buildings Used For? Here’s the Mod Fam Quick Guide:

During its various stages, Chichén Itzá represented a cultural fusion, and combines elements of various regions. Researchers first pointed out architectural connections between Tula and Chichén Itzá in 1887 (both have similar columned areas, spatial arrangement, relative location of the ball court, etc.) Sculptures, the reclining Chac Mool in particular, reinforce these connections between the Toltecs and Itzá of Yucatán. Significant debate over the source of these similarities (and their complete absence at sites between the two) continues to the present.

Between A.D. 800 and 1100, its area extended more than 25 square km., and served a population of more than 30,000.

The Maya of Yucatán were overrun by Central Mexican groups (likely the Toltecs) after A.D. 900. These groups ruled from Chichén Itzá until about A.D. 1200-1250, and brought with them many of the practices and iconography of Tula and Central Mexico (Chac Mool statues, pillared palace, warrior pillars, and a more intense focus on human sacrifice). After A.D. 1250, Chichén Itzá was abandoned, and Mayapán rose in prominence as Mayan lords again ruled the Yucatán. Mayapán, too, fell around 1450, and by the arrival of the Spanish, any regional authority (beyond the immediate, local level) had disappeared from Yucatán.

- El Castillo or Kukulkán – El Castillo rises 24 meters (78.74 feet) above the surrounding grounds. Large serpent heads adorn the base of the North staircase. Depictions of shells on the roof refer to the wind.

- Temple of the Jaguars – This temple sits at the far South end of the East side of ball court (not the South Temple). The interior depicts battle scenes in front of a small town.

- Ball Court, along with the North and South Temples – This ball court is the largest ball court in all of Mesoamerica, and dates to the Maya-Toltec Period of development. The goal of the game was not only to pass the ball through the small stone rings on either side of the court, but to keep the ball moving back and forth in imitation of the planets and solar bodies. Each of the temples to the North and the South are decorated with different reliefs, some depicting families or clans, warriors, sacrifices, decapitation, and other practices.

- El Tzompantli or Row of Skulls – The Row of Skulls is a copy of those found in Central Mexico (the Aztecs also had a number of skull rows or racks).

- Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars and the Platform of Venus – Near the ball court, both platforms depict different images, animals, and practices. The former depicts eagles and jaguars eating human hearts, while the latter depicts the plumed serpent with claws of a jaguar.

- Sacred Cenote – The sacred cenote of Chichén Itzá is a fresh-water well from which sacrifices and other offerings have been recovered. Most of the recovered sacrifices at this site were children, and other offerings include gold disks, jade, obsidian, wood, textiles, and shells.

- Temple of the Warriors – Small statues and a Chac Mool sit above the steps to the temple of the Warriors. This temple is visible from the Kukulkán Pyramid and the direction of the ball court. The jaguars, eagles, and mythical animal in the murals are all depicted eating a human heart. The Chac Mool at the top of the stairs may represent a mediator or intermediary between the Maya and the gods. Murals inside the temple depict daily life, human sacrifice, and battles.

- Temple of the Tables and Temple of Chac Mool – Murals in these temples depict jaguars and seated male figures on jaguar thrones. The Temple of Chac Mool is located beneath the outer structure of the Temple of the Warriors, and the Temple of the Tables sits just to the North of both, on a separate platform.

- Group of a Thousand Columns – This enormous, column-supported roofed area likely served some military or training function. More than 2,000 images of armed warriors mark each of the supporting pillars.

- The Market – Like the Group of a Thousand Columns, the Market was reserved for nobles or warriors, or both. It is not related to an actual market.

- The Observatory – The observatory was constructed at the height of Chichén Itzá, between A.D. 900 and 1100. Images of Chac adorn the building.

(Information from Keen, Benjamin and Keith Haynes. A History of Latin America. 8th Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2009. López Austin, Alfredo and Leonardo López Luján. Mexico’s Indigenous Past. Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 2001. Martos, Luis. Chichén Itzá: Historia, Arte y Monumentos. Mexico, D.F.: Monclem Ediciones, S. A. de C.V., 2008.)

[…] Ek’ Balam and Chichén Itzá Ruins […]